As with any disaster preparation leaving your home should be a last resort. I only live on the 4th floor so evacuating is not a terribly unbelievable scenario. Pocket-size emergency kits are fun mental exercises but there's not many scenarios where you just can't carry a backpack or duffle bag.

I split this box of stuff between stockpiling that is left at home, and stuff that can be carried by one person. The former includes stuff like water carboys and a few weeks worth of food, items that are rotated out and treated as a normal pantry. The latter mostly includes items that fix unpleasant situations (rain, bugs, cold) as well as important personal documents.

contents

Pocketknife

Mini Boxcutter

IDF Water purification tablets

FOX40 whistle

Ferrocium rod

compressed gauze, Israeli compression bandage x2

P-51 can opener

AAA to AA battery converters

Sppon, fork, chopsticks

anti-histamines, paracetamol, salt tablets

Instant towels

Pencil

needle and thread

Sunscreen x4

Gloves

N95 Masks x2

Mylar blanket

Disposable poncho

2L water bag

5L water bag

Instant fuel

Rechargable lantern/portable battery x3

USB LED lights x5

other

Hill People Gear Tarahumara backpack

10L collapsible water carboy

1L canteen x2 (not pictured)

instant rice

instant soup

shelf-stable bread

collapsible 25L dufflebag

extra clothing (not pictured)

extra phone batteries

personal documents, money

PC HDD (not pictured)

Probably overkill in regards to water at around 15 liters in total.

Add:

mosquito head net

pink bismuth/loperamide

CAT tourniquet x2 (in the US)

hemostatic agent (in the US)

trauma shears (in the US)

SAM splint

helmet (essential east asian

silm bic lighters

Fenix E11 replacement

right-angle flashlight /headlight (in the US)

wood gas stove (in the US)

mess tin

high-vis clothing

waders (after recent floods)

picardin/DEET

ear plugs

solar panels? battery banks?

Stockpile:

batteries

retort pouch food

Chlorhexidine/Ethanol/Chlorine

plastic bags to shit in

beans? (not cheap in japan)

gas canisters? (not really a normal consumable item)

scrap firewood/charcoal (latter more likely to see normal use)

hard exceptions:

no exothermic lighting sources. They require constant monitoring, are a perennial fire hazard, some like kerosene lamps emit fumes

no pasta or non-instant rice. They take a long time to cook. Not ideal when fuel or water is limited.

no alcohol stoves. they're one jolt away from a molotov cocktail, stoves on methanol create invisible flames, impossible to refuel while running, not very hot, affected heavily by wind.

shelf-stable bread with nuts or shortening goes rancid in 2 or 3 years. most instant noodles too.

back to top ⤴

Prepping is the big short: a bet not just against a city, or a country or a government, but against the whole idea of sustainable civilization. For that reason, it chafes against one of polite society’s last remaining taboos — that the way we live is not simply plagued by certain problems, but is itself insolubly problematic.

2/12/2021

There's numerous chin-stroking columns about the incestuous relation between rural america and prepping. Religious doomsday doctrine, widespread economic decay, and fanatic libertarianism all come together to really appeal to SunnyD-Americans. They are losers of the transnational bidding war, first to the Japanese, then Chinese, and now the Vietnamese. They can work faster than us, cheaper than us, ignore workplace safety better than us. Their fate is predetermined no matter how hard they try in Bethlehem or Toledo. Within those communities left behind under globalization people seem to prefer fantasies about the end of the earth than any meaningful alternative. Scenarios where their agency is unquestioned, the conflict of living and dying is more explicit than balance subtractions or the economic alienation of their rural town. Sure a world without other people would be exciting. Urban exploration every day, larceny without the cops crawling up your ass, gleefully entering places because you couldn't like a child on a chair reaching into an adult-height cupboard. No more debt, commuting, or after-work gatherings. While running through these scenarios in your head divorcing yourself from a disagreeable reality, you transition into this odd mental state of hoping the apocalypse won't be catastrophic or even unpleasant, but that it will be something to look forward to. Society becomes a true meritocracy when everyone else is dead. Welcoming a nuclear holocaust is antecedent to becoming a homeowner for the first time. For people who experience structural violence everyday, a post-money post-society existence probably seems like something worth preparing for. When a vendor was asked

if they could envision using the prepping supplies they were selling she replied "I don't know. But If there was an apocalypse, I'd be running for the flash. I don't wanna be a cockroach." Some people fantasize about being that cockroach.

In 2020 the apocalypse seemed a lot less desirable. I often joke that my life is directly tied to my hard drive: that our health is one. All the nothings contained within carries more meaning to me than it should.

I can now say the same with other people. Yes people, the thousands of mechanical heads you used to see bobbing along in Ikebukuro, the kind that avoids your eyes on the sidewalk like they're magnetically incompatible, the black masses that approach the station every morning like hungry flies. I live for them, I live because of them. This epiphany didn't come after nervously watching the river swell on twitter during a hurricane or hunkering down for 6 months during a global outbreak. I'm not particularly concerned about my health, when it's time it's time. Instead it was the weekly runs to the store that suddenly shook me awake.

Every time I walk down my neighborhood I see the same views: the same grey buidlings, the same housewives on bikes, the same deliverymen, the same couples heading to the park. I'm transported back when I was visiting this country on holiday, dodging the tourist locations in favor of a back street or a placid neighborhood. I would wipe myself clean to imagine a life and a routine here, the daily views rendered monotonous, the store routes, the secluded corners with good views. I wonder what the young couples' apartments look like, what interior arrangements they've propped together. What the roving bicycle gangs of unsexed teenagers are up to, what the kids are thinking as they walk home in uniforms, what concealed interests the anonymous salarymen look forward to with green onions sticking out of grocery bags like field radio antennas, this neurosis is racing through my mind as I head to the vegetable stand. These thoughts keep me sane because no matter how much I try, I can't excite myself into a frenzy indoors with trifling little hobbies or attention-grabbing TV shows. I need other people to stay well, to remind myself that I do not exist in some kind of 10x10' vaccuum.

And so can you imagine fantasizing for a solitary apocalypse? It just didn't make sense anymore. No matter how distressing and shameless and reprehensible the outside world is surely it isn't any better alone. I don't live for just myself.

10/3/2021

These feelings I had were reflected in the book How to do Nothing

with the story of the Seven Storey Mountain:

(Thomas) Merton arrived and was accepted at the Abbey of Gethsemani in rural Kentucky in 1941. So much did he desire solitude that he spent years petitioning to become a hermit on the monastery grounds. In the meantime, between his duties, he found time to keep a journal that eventually grew into a book. In 1948, the same year he was ordained as a monk, he published the autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain

, which besides chronicling his move to the monastery was an embodiment of contemptus mundi—a spiritual rejection of the world. It contained, as Rice describes it, the “evocation of a young man in an age when the soul of mankind had been laid open as never before, during world depression and unrest and the rise of both Communism and Fascism, when Europe and America seemed destined to war on a brutal and unimaginable scale.” The book sold tens of thousands of copies within a few months of publication and was only kept off The New York Times bestseller list on the grounds that it was considered a religious book. It went on to sell multiple millions of copies.

But only three years after its publication, Merton wrote to Rice, disowning the book: “I have become very different from what I used to be…The Steven Storey Mountain is the work of a man I never even heard of.” It had to do, he said, with an epiphany he had while accompanying a fellow clergyman on a trip to Louisville:

'In Louisville, at the corner of Fourth and Walnut, in the center of the shopping district, I was suddenly overwhelmed with the realization that I loved all these people, that they were mine and I theirs, that we could not be alien to one another even though we were total strangers. It was like waking from a dream of separateness, of spurious self-isolation in a special world, the world of renunciation and supposed holiness.'

From that point until the end of his life, Merton published a score of books, essays, and reviews that not only commented on social issues (particularly the Vietnam War, the effects of racism, and imperialist capitalism) but also lambasted the Catholic Church for giving up on the world and retreating into the abstract. In short, he participated....Removal and contemplation were necessary to be able to see what was happening, but that same contemplation would always bring one back around to their responsibility to and in the world. For Merton, there was no question of whether or not to participate, only how.

back to top ⤴

I've been preparing an emergency bag lately. It's a boring little pile of dollarstore treats and employer-supplied disaster goods. I used to be big into camping/wilderness survival as a kid, and going through the motions have really brought those memories back. Playing out scenarios in my head, logging shopping lists, drawing out neighborhood plans. The idea is to stock PPE, important documents, and a couple days' worth of food in preparation of evacuating to a school or community center. You'd think god himself hates Japan, as the weather is relentless. Every year there's hurricanes, floods, earthquakes, a joyful salad of horror splashed across news screens. Last year's hurricane got me shitting my pants, and apparently my sister's friends did come home to a flooded apartment.

I've been preparing an emergency bag lately. It's a boring little pile of dollarstore treats and employer-supplied disaster goods. I used to be big into camping/wilderness survival as a kid, and going through the motions have really brought those memories back. Playing out scenarios in my head, logging shopping lists, drawing out neighborhood plans. The idea is to stock PPE, important documents, and a couple days' worth of food in preparation of evacuating to a school or community center. You'd think god himself hates Japan, as the weather is relentless. Every year there's hurricanes, floods, earthquakes, a joyful salad of horror splashed across news screens. Last year's hurricane got me shitting my pants, and apparently my sister's friends did come home to a flooded apartment.

The contrast between the US and Japan is really interesting within the context of disaster preparedness. Disaster relief is a very centralized affair over here, dependent on government and NGO resources in a particular location rather than local cooperatives (not like US preppers have that in mind either). As such, emergency bags are much more focused on personal protection and hygiene for when you're stuck in a stadium with other evacuees, like an unpleasant open air hostel. There's no fire starters, water filters, or animals traps for this reason: it's presumed that it will be provided by institutions or organizations. I think the moment Japanese people are necessitated to stay at home for long periods of time without relief, it's time to call off the whole "country" thing. You saw the same centralized relief effort patterns after the Hanshin

and Tohoku earthquakes.

To presume otherwise means that the disaster is severe enough that the state,military, and NGOs are completely unable to provide relief or outright evacuations to a centralized location, at which point it's right to assume that Japan has ceased to be a pleasant, functioning society.

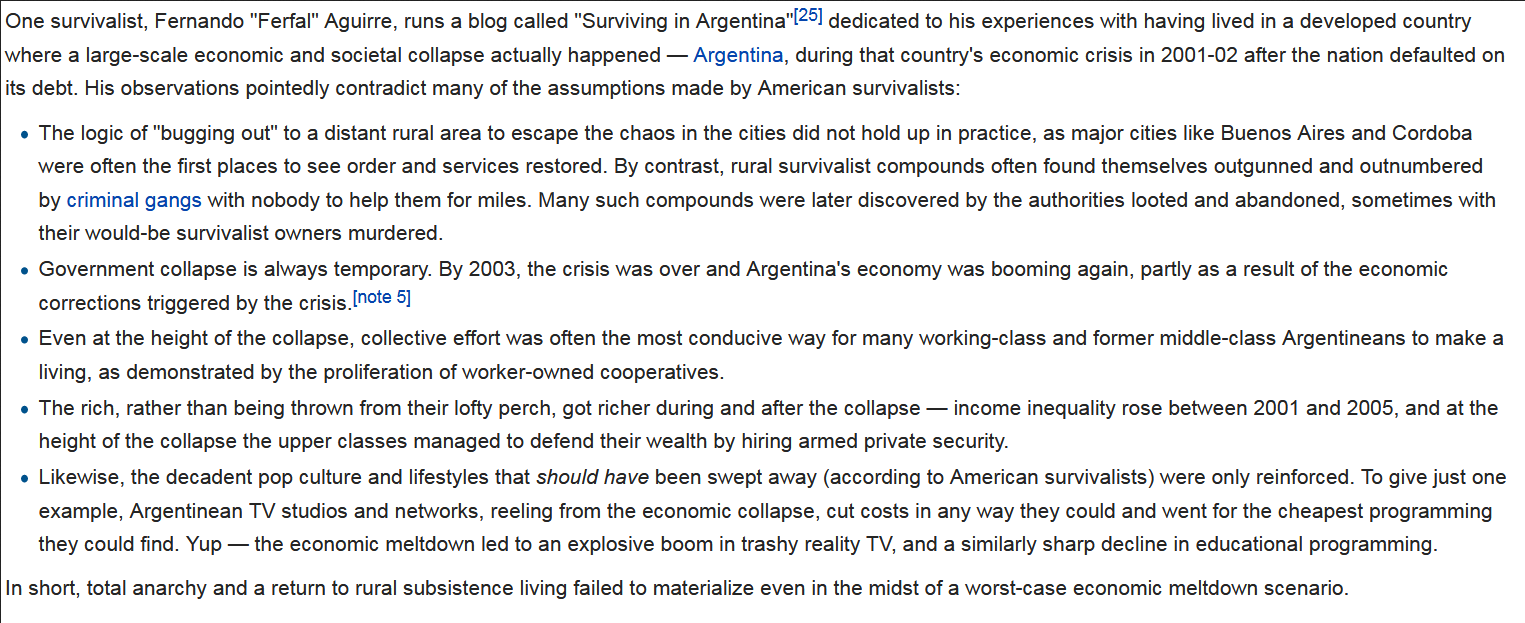

So everything in my bag is short term; a bridge between disaster and settling at an evacuation center. In contrast, US preppers have a rabid preoccupation with the "rugged individual," really a perfect allegory for the uniquely American "fuck you, got mine" ideology, one twisted into scenarios where someone is joyfully protecting their property through force. The fantasies go that after a disaster all services and utilities cease to function, therefore all needs have to be met on an individual level at home. Stockpiled food, power generators, water carboys, and guns are analogous to American prepping. Does this have a basis in reality? Only partially. Katrina and Puerto Rico come to mind where the state was utterly unable to provide for citizens following a disaster. You almost never see gas stoves or tents in American bugout bags for this reason; everyone figures they can just collect brush or firewood for use at home. Everything is in bulk and set for long-term settling before disaster relief in the US. There's several fundamental issues this perspective retains, mainly a lack of historical contemporary precedent other than unverified Serbian civil war interviews. Events tracing conventional TEOTWAWKI scenarios unravel rugged survivalist rationalizations endemic to American preppers.

Turns out pandemics, like most disasters, aren't terribly sexy. Everyone's stuck indoors because it's the sensible thing to do and the benign issues of spotty internet and boredom gloss over any fears about total societal collapse. Cultural norms haven't unraveled into barbarism either, people panic buying paper goods at the supermarket will still grimace at your CBRN katana cover. The sensible thing to do right now is to wear filtered half-masks and face shields but everyone hasn't. Social conventions haven't fallen away to the bottom line of pragmatism just yet. And it probably never will. People in warzones are above all eager to reclaim their previous lives. Governments also tend to be more inept at mobilizing 1984 fantasies, even the outwardly fashy ones. Flat out denial seems to be trending among world leaders from America to Brazil in the most depressing cultural intersection since slavery. One of the many recent epiphanies I've had under this techno-dystopia is that most democratic institutions don't really care about people.

Turns out pandemics, like most disasters, aren't terribly sexy. Everyone's stuck indoors because it's the sensible thing to do and the benign issues of spotty internet and boredom gloss over any fears about total societal collapse. Cultural norms haven't unraveled into barbarism either, people panic buying paper goods at the supermarket will still grimace at your CBRN katana cover. The sensible thing to do right now is to wear filtered half-masks and face shields but everyone hasn't. Social conventions haven't fallen away to the bottom line of pragmatism just yet. And it probably never will. People in warzones are above all eager to reclaim their previous lives. Governments also tend to be more inept at mobilizing 1984 fantasies, even the outwardly fashy ones. Flat out denial seems to be trending among world leaders from America to Brazil in the most depressing cultural intersection since slavery. One of the many recent epiphanies I've had under this techno-dystopia is that most democratic institutions don't really care about people.

I get it though, there's a definite allure to the level of agency during a dire situation. Fantasizing about a disaster is a refreshing contrast to our numbers' based day-to-day of productivity, consumption, and death. A plane crash or shipwreck exists as a vacuum of value systems. I'd love to be a Crusoe or Robeson, blazing my own trail of self-determination free from the long-winded conventions of modern society. The thrill of being intimately involved in your daily life is why primitive technology

videos and wilderness survival shows are so popular, and why Anarcho-Primitivism is so memeable.

A big axis to that contradictory freedom is money. "Time is money," despite the milieu of cultural attitudes it occupies, pretty well sums up the intimate bond between capital and human morality. Time, any time, can be spent on producing capital. The one enveloping force behind everything in our daily lives, reduced down to "productivity." If not producing you're occupied with something surely lesser, a childlike value system ubservient to cold hard cash. Getting an education is increasing your human capital. Learning a new language is increasing your human capital. "Experience" adds to your human capital. Forgo the interactions that make you a better informed, more well rounded human being, that is secondary to your value to the enveloping economic system we live under. You don't match up? You are inherently worth less as a human being.

Modern arrangements of labor are incredible. Living in a core country I can sit around in a cubicle shifting around numbers on a spreadsheet and pay for a meal in an hour or two even after a millionaire takes a cut of my economic productivity. My breakfast every morning is a great big amalgam of production, logistics, and retail that somehow manages to employ thousands and drive down prices. But still I'm left wondering who is compromising in order to meet those prices. I think normal people today can see beyond the evangelizing of transnational trade and economies of scale. The promises of austerity and technological progress seem like lofty fantasies akin to abandoning Earth for another planet instead of any other rational solution. While visiting Machester at the height of industrialization in 1815 Alexis de Tocqueville wrote "From this foul drain, the greatest stream of human industry flows out to fertilize the entire world," by far the most flattering description of Manchester it has ever received. The current Green Revolution in India, spurred by modern agriculture practices brought increased yields but also a national farmer suicide crisis and widespread environmental degredation. How does Amazon meet their logistical quotas, how does modern agribusiness gather their labor force in an increasingly unfavorable job market, how are apples 49 cents after growing, picking, packing, and delivery? Ultimately it's people who are making those compromises, whether it's slaughterhouse workers doing meth to up their productivity after Tyson slashes pay

or farmers nervously watching seed prices. Workers are the martyrs of $1.99 TV dinners.

Today you don't construct dwellings, you pay rent. Why own tools if you have a desk job? Why pay attention to your food when you can just drive to the corner store? Why buy things when they will surely depreciate in value? Just like that, directly rewarding interactions are replaced with numbers. Your work is worth this much. You're existing here? That costs this much. That item on the shelf? That took this many hours to produce. Not in this country of course, one where human life is inherently worth less. Preagricultural societies did not have these distinctions, and the line between adolescent play and work simply did not exist, the former would transform into the latter as the child took on greater responsibilities:

The hunter-gatherer way of life had been skill-intensive and knowledge-intensive, but not labor-intensive. To be effective hunters and gatherers, people had to acquire a vast knowledge of the plants and animals on which they depended and of the landscapes within which they foraged. They also had to develop great skill in crafting and using the tools of hunting and gathering. They had to be able to take initiative and be creative in finding foods and tracking game. However, they did not have to work long hours; and the work they did was exciting, not dreary. Anthropologists have reported that the hunter-gatherer groups they studied did not distinguish between work and play—essentially all of life was understood as play.

In sum, for several thousand years after the advent of agriculture, the education of children was, to a considerable degree, a matter squashing their willfulness in order to make them good laborers. A good child was an obedient child, who suppressed his or her urge to play and explore and dutifully carried out the orders of adult masters. Such education, fortunately, was never fully successful. The human instincts to play and explore are so powerful that they can never be fully beaten out of a child. But the philosophy of education throughout that period, to the degree that it could be articulated, was the opposite of the philosophy that hunter-gatherers had held for hundreds of thousands of years earlier..

And purpose is alluring. I can live my life utterly uninvested in my surroundings and the globalized economy will pander to my apathy offering morally questionable commodities at similarly questionable prices. Practicing "ethical consumption" today requires a frankly neurotic level of awareness in slavery, outsourcing, production methods, unionbusting, and monopolies that most leaded-gasoline tainted boomer neurons are incapable of retaining. The conditions at which you live and die feel less proximate, your agency under a set of qualifiers. Self-indulgently thinking about the end of days is a strange fantasy but it pairs well with the dystopian nightmare the US is currently living under.

/r/preppers, finding itself rejuvenated with justifiably concerned people, has been lit ablaze with righteous masturbatory posts about peering over sickly bodies panic buying. And yet posts about donating PPE to hospitals and reaching out to neighbors dot every other post in between post apoc fantasies by posters itching for a justification to shoot someone.

But no matter how intimate communities become, wider issues like this pandemic transcend packages of rice and wet wipes. Reality has made Contagion

seem like a civil servant's optimistic fever dream. This crisis, through all the stunning headlines and statistics has shown that the roots of our cultural anxieties should lie not in the darwinian barbarity of desperate people, but the structural violence of normalized life. With 783,000 dead globally we have entered a new phase of life, one not profoundly deviant from the norm but one that is rapidly accelerating towards an exaggerated parody of reality. Inequality is widening further with $637 billion thrown to the world's wealthiest.

The 108 million Americans who are unable to work from home

are explicitly threatening their own lives by commuting. In August the S &P hit its all-time high while unemployment hauled its corpse over 10.2%

Eviction estimates rocket into the tens of millions

while both houses of congress sits on their hands. The preexisting conditions of American society are beginning to take shape in a way that cannot be dismissed simply as "minority issues." Juxtaposed with the spectres of police violence and an administration largely unresponsive to 180,000 dead, the pandemic has shown Americans that the current arrangement is not just intolerable to the poor and the brown. Like their persistent failures to provide an effective answers to global terrorism, financial crises, global warming, and wealth disaprities, institutions have unsurprisingly failed to contain coronavirus.

Originally published in volume 1 of the zine EARRATMAG

on 4/17/2020

back to top ⤴